“But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.” – George Orwell, Politics and the English Language

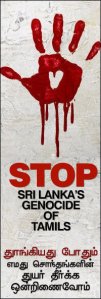

Genocide has become such an emotive and powerful word -- it recalls the horrors of the Holocaust and Rwanda in our popular psyche, and so is seen as the crime that demands immediate international intervention among the public at large.

Hip Hopster M.I.A should stick to singing and not dabble in anti-genocide advocacy for Sri Lanka, or so her not-so-hip critics charge. They claim this is the preserve of ivory tower denizens, or comparably able minds. Not even Arundhati Roy is welcome at this exclusive club. Volleys of withering criticism have been directed by mostly Sri Lankans, seemingly concerned for the plight of Tamils, but really worried about the conflict moving beyond the counterinsurgency/counter-terrorism context or the obscurity of civil war.

I am neither an Arundhati Roy nor a Palitha Kohona, but somehow I think the former would be more receptive to my attempt at making sense of the politics around the G-Word.

Note: I am not going to dispute or dismiss genocide as it relates to the Sri Lankan case.

Why?

Because an official genocide determination has not mattered and likely never will (at least not in any consistent and meaningful way) for the victims of mass atrocities.

But before I go into length about the hobbling nature of the politics and popular western perceptions behind suppressing and or preventing such slaughters in ‘far away’ lands let me skim over the legal niceties on genocide.

A Convention at Odds With Itself

Raphael Lemkin, who came up with the legal and politico-social framework for defining genocide and helped father the Genocide Convention, was driven not only by the Holocaust but also by the horrors perpetrated by the Turks on the Armenians. Even to this day, the G-Word is not officially used in many parts of the Western world in reference to the Armenians.

The Genocide Convention, which provides the legal basis for an international response to this crime, is its own undoing. The definition(s) and applications of it are fraught with challenges when applied in the real world.

The physical acts of genocide specified in the convention include:

“(a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Since day 1 the Genocide Convention has been in conflict with itself: between "actus reus" (physical) and "mens rea" (state of mind).

The state of mind component, i.e "intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group," is what differentiates an act of genocide from any other mass atrocity.

As the ICTR (International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda) noted, “intent is a mental factor which is difficult, even impossible, to determine', and that in the absence of a confession from the accused, intent can only be 'inferred from a certain number of presumptions of fact”.

Intent should be distinguished from motive. For example, the intent for committing the physical acts could be counterinsurgency (CI), or its contemporary [counter-terrorism (CT)] whereas motive could be averting secession. Or, intent could be ‘whole or partial destruction’ (as CI measures in the ‘third world’ show) and motive could be national security. This distinction between intent and motive was one of the drivers in the dismissal of genocide charges in Darfur by the ICC. The absurdity behind this word game is discussed here.

Part II will be published shortly.

No comments:

Post a Comment